(December 7, 1907 — March 19, 1987)

Article by Matt Rovner

It appears that Matt Rovner’s series of articles on Arch Oboler is expanding like the titular monster of Oboler’s famous radio play “Chicken Heart”1. Matt brings you the second part of a special ongoing series on the radio drama, filmmaking, and life of writer-producer-director, Arch Oboler. In the first part of the series, Oboler made great strides in his radio career with the support of the manager of NBC’s script division, Lewis Titterton. He also attracted the attention of Hollywood. In this second part, Oboler attempts to take his radio career in a more commercial direction while preserving his artistic freedom and balancing a nascent film career.

April 9, 1940 … Dear Lewis [Titterton] … MGM has turned over the Ethel Vance2 novel “Escape” to me expecting to get a complete screenplay3 inside of two weeks so that they can go into production at once. The opportunity is so exciting that I dove right in … As ever, Arch Oboler 4

Lewis Titterton, Arch Oboler’s staunchest supporter at NBC, would have appreciated his protégé’s excitement at writing Escape (1940). It was Oboler’s first screenplay and an overtly anti-Nazi story. When writing for Lights Out (1936-38), Oboler had smuggled anti-fascist stories across the airwaves. Now, he could more directly attack the dehumanizing Nazi regime he so passionately loathed.5 The following are scenes from Escape, which demonstrate Oboler’s unique ability to combine suspense, the macabre, and melodrama into an emotionally satisfying and socially conscious experience:

It is night. Freezing cold. It is the late 1930s in Nazi Germany. Inside a concentration camp, Mark Preysing (Robert Taylor) and Fritz (Felix Bressart) are carrying a coffin to a truck. Inside the coffin is Mark’s mother, Emmy Ritter (Alla Nazimova). Emmy is alive but in a coma. There are only two people aware of this fact, Mark and Dr. Ditten (Philip Dorn), the doctor who deliberately induced the coma in order to help Emmy escape an unjust and hideous execution. Mark and Fritz lower the coffin to the ground, then Fritz opens the rear doors of the truck. As they lift up the coffin, they hear the curt command “STOP! Put that down.” A Gestapo Officer (Henry Victor) strides over to Mark and the coffin:

Gestapo Officer: What are you going to do with this?

Mark: We’re going to bury her.

Gestapo Officer: Do it here! We have a place in the back for it!

Mark: But, we have permission to take her, to bury her outside …

Gestapo Officer: Oh. Have you?

Fritz (unfolds a document): Here! Here is the —

Gestapo Officer (snatches papers away): I can read! (he slowly begins to examine

papers).

Mark: Would you mind hurrying, please —

Gestapo Officer: She’s dead, isn’t she? Then what’s the hurry? (he looks down at the

coffin) And that is the coffin?

Mark: Yes.

Gestapo Officer: I will have to see the body!

Fritz takes the lid off the coffin to reveal Emmy, apparently dead. When the lid is replaced and Mark and Fritz begin lifting the coffin again, the Gestapo Officer shoves it to the ground with his foot and demands that the lid of the coffin be nailed down. Fritz is clumsy and slow as he tries to nail down the lid. Mark snatches the hammer and nails and makes a quick and competent job of it. Finally, Mark and Fritz load the coffin containing Emmy into the truck and drive away.

Their truck is on a snowy stretch of back country road, and it is rocked by the wind. Mark demands that Fritz stop the truck so that he can remove his mother from the coffin before she suffocates. Not understanding the situation, Fritz refuses to stop the vehicle. Mark throws the emergency brake and gets into the back of the truck. Once Mark is in the back of the truck, Fritz speeds away. Mark pries the lid off the coffin and wraps his mother in a blanket. She is not responsive. Fritz stops the truck because the road ahead is blocked. Emmy is still not responsive, and at this point Mark becomes despondent.

Mark: She’s dead.

Fritz: Dead? What’s the matter with you, Mr. Mark? Of course, she’s dead! Now,

please come out, Mr. Mark.

Mark: She was alive, Fritz …

Fritz: Oh please, Mr. Mark, you must try to keep your mind away from what

happened. Come on, I’ll help you cover her over again.

Mark: No, no. Leave her alone.

Fritz: Please Mr. Mark, stop acting like a child! Your mother was dead, she is dead,

and nothing you can do — (he suddenly cries out and recoils)

A close up of Emmy’s face reveals tears sliding from under her eyes and down her cheeks. Unlike the doomed protagonist of Oboler’s Lights Out radio play “Burial Services”, Emmy Ritter is saved.

Escape was directed by Mervyn LeRoy6 , who also hired Arch Oboler to rewrite the film. Oboler’s initial excitement turned into impatience when the writing assignment stretched out due to the demands of the Hollywood star system7 , “August 22, 1940 … Dear Lewis … Believe it or not, I’m still working on ‘Escape’; added scenes, this time, to help the [Norma] Shearer close-up ego. Apparently there’s no escape from ‘Escape’ but a shotgun, a noose, and a bottle of cyanide …”8 Despite his restlessness, Oboler must have been pleased with the New York Times’ ecstatic review:

…this is far and away the most dramatic and hair-raising picture yet made on the sinister subject of persecution in a totalitarian land, and the suspense which it manages to compress in its moments of greatest intensity would almost seem enough to blow sizable holes in the screen. Propaganda? Well, of course—if you choose to label a picture which tells a documented story with that word. But this film is something more than a shocking, repulsive account of brutality and inhumanity directed against helpless beings. Rather it is a story of courageous opposition to a system which attempts to crush the freedom of mankind, a vivid and inspiring tale of a small but significant cooperative effort to defeat the forces of oppression…9

Oboler estimated that about seventy percent of what he wrote ended up on the screen,10 “I had to revise what had been written by many others up until then, and, naturally, in my writing ego, I went off on my own.” 11 Some of what was cut were Oboler’s overt warnings to the film’s audience:

Ditten: My regards to America! And when you get back, remember this: it took you a long time to get what you have there and it’s easy to throw away what you have for the promise of something better. Then, when the promise is broken—you never get back what you had. If you give up your democracy even for a moment—it is gone forever.12

Oboler’s admonition is severe and concise, but his penchant for didacticism served him better on radio and, as we’ll see, could interfere with the pacing of his own films when no one else had the power to cut his dialogue. Ultimately, he was “… grateful that what was left was left; sufficient to make an entertaining picture with a kernel of meaning …”13

Oboler reveled in his freedom to write meaningful stories. In a letter to Maxine Block, the editor of Current Biography, he broadcast his pioneering spirit and excitement about seizing many “first” opportunities:

Thank you for the copy of CURRENT BIOGRAPHY in which my sketch appeared; here are some additional pertinent facts: Random House has just published a book of my plays, the first book of its sort ever put out, titled “Fourteen Radio Plays by Arch Oboler.” … I have just done my first motion picture writing job, “Escape” for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer … At the present time I am also writing, directing and producing a series of my original radio plays for Procter & Gamble under the title of “Everyman’s Theatre”. This program is the first dramatic series on the air where the writer has been given absolute complete freedom by a national sponsor … Very truly yours, Arch Oboler14

As disclosed in part one of this article, Oboler came to regret Everyman’s Theatre as a career move that was “wrong from the beginning”.15 In his retrospective interview on Same Time, Same Station, Oboler placed most of the blame on the contact man16 from Procter and Gamble’s advertising agency Blackett, Sample and Hummert (BSH). Oboler may also have been thinking of the discord that Everyman’s Theatre caused in his relationship with Lewis Titterton. Titterton was a man that Oboler still expressed admiration for—some thirty years later—on Same Time, Same Station. The correspondence between Oboler and Titterton regarding Everyman’s Theatre begins on a hopeful note, but soon sets the tone for the disappointment and disquiet that came to characterize Oboler’s commercial debut as a radio auteur:

June 6, 1940 … Dear Lewis: I’m sure you’ll be pleased to hear that I received a letter of confirmation from Blackett Sample & Hummert confirming their purchase of Arch Oboler’s Plays to start on the Red network17 [of NBC] October 4th, Friday, at 9:30 PM. I made the conditions very difficult, insisting that I have the same freedom that you gave me on the sustaining series and, unbelievably, they agreed … It’ll amuse you to know that one of the conditions I made in the contract was that I go on the Red network; oh for Pete’s sake, this letter is a fine hash but I’m sure you’ll get that I’m pleased and grateful … Cordially, Arch Oboler18

Contrary to Oboler’s expectations, Titterton was neither pleased nor amused; instead, he thought his protégé ungrateful, at the very least. According to Titterton, prior to Oboler’s letter, he learned of the sale to BSH “obliquely” through an announcement in Variety and a phone call from William Murray, the head of the William Morris Agency19 in New York City.20 Even worse, Titterton also pointed out that NBC, itself, had also been trying to sell Arch Oboler’s Plays to Procter and Gamble, “… I still am of the opinion that, even if you did not intend to let NBC participate in the sale to P. & G. on which they had been working, you had an obligation to let us know what was happening …”21 Lewis Titterton’s letters to Oboler reveal a paternalistic pride and disappointment in his protégé, but also genuine distress:

It was a source of immense satisfaction to me that the very vigorous efforts put forth tirelessly for a period of over a year by all the offices of NBC have resulted in putting you, from a good but comparatively obscure radio writer, into the position of a man whom a major sponsor22 would buy in this way …

… I must confess to a personal feeling of real disappointment that the man I had counted a friend and a leader in American radio should think so little of those with whom he has been associated in the development of his own place in American radio that he would enter into a major commitment without even informing them that he was so doing, much less indicating that he felt any gratitude to them for the labor they had put forth over a long period of time.

I have no less respect today for the talent of Arch Oboler than I have had before, but I find it hard to have the same esteem, affection and respect for the person. Faithfully yours, L H Titterton.23

Oboler tried to explain the situation to Titterton as a misunderstanding:

… [i]n our year of close work together you’ve never known me to lie and it follows that I’m telling the truth now when I say that the Variety story appeared before I had definite confirmation from the sponsor … As far as Murray’s phone call to you on [June] 3rd is concerned, I have no control over what their Hollywood office wires to them. I told the William Morris office to let you know that the commercial [prospects] looked very good and consequently I didn’t want to hold up the summer series [Arch Oboler’s Plays] any longer. But I definitely had no program at that time for which to thank you …24

Further, Oboler explained to his friend that he did not know that NBC was trying to sell Arch Oboler’s Plays to P. & G. through BSH; in fact, Arch Oboler’s Plays was a “virgin idea” to the BSH contact man.25 Oboler also vented some of his own frustrations to Titterton:

As far as your apparent resentment for not calling NBC in is concerned, all I ask you to do is to stop being a good company man for a moment and face the facts. I went off the air at the end of March26 and since that time … There was great blank empty silence …27

In spite of Oboler’s contention that NBC dropped the ball, he expressed the following:

… I was very grateful to the National Broadcasting Company (and I have evidenced that gratitude by insisting contractually that the program be released only on the Red network of NBC, jeopardizing the deal by said insistence) but, at the same time I feel that by giving the National Broadcasting Company, for a year and at a very nominal figure, a prestige program which reflected glory on all of us, I earned my money honestly and balanced the scales to such an extent that I can face the facts quite calmly and content … Cordially, Arch Oboler.28

In his book Oboler Omnibus, Oboler recounted that NBC had actually thought that Arch Oboler’s Plays

was unsalable:

The network sales department had been trying to sell the Arch Oboler’s Plays series during its entire year on the air, but such dramatic concern about matters of interest only to foreigners in Europe was definitely unsalable, I was informed;—but one day a young hillbilly by the name of Jimmy Parks29 phoned me from Chicago to ask me if I could go on the air, with the sort of plays I had been doing, for money.30

From Oboler’s perspective, NBC had let him down. And, he needed to escape the potential trap of continuing to write and direct sustaining programs for little money while bringing NBC great prestige with these programs. Oboler feared being exploited like the lifeless workers of his radio play “Profits Unlimited”, where the laborers repeat the mantra “like work here, no complaints, like work here, no complaints”:31

It is ridiculous to attribute some sort of mystic holiness to the radio dramatic series that is broadcast not-for-money. There is no reason, in a world which, for the most part, continues to have some sort of monetary system, that one should not be paid for work done to the limit of one’s creative abilities.32

In other words, Arch also needed the money. He had recently contracted with the maverick, esteemed, and expensive architect Frank Lloyd Wright to build his dream house in the hills of the Santa Monica mountains. Fortunately, the money was good, exceptionally good. Procter and Gamble contracted with Oboler for $4,00033 per half-hour episode, and Oboler believed that he would retain his “absolute complete freedom.” Despite his apparent good fortune, tensions and corporate politics continued.

On July 10, 1940, Wallace “Wally” West of the NBC Press Department wrote Oboler the following: “I’ve run into a peculiar situation here regarding your new series for P. & G., and think I’d better give you an off-the-record look-in on it.”34 Wally West was another one of Arch Oboler’s supporters at NBC. Oboler was grateful to West for his publicity, and he extolled West’s talents to John F. Royal, NBC’s Vice President in charge of programs:

… You know the terrific amount of editorial attention my series got and I wanted you to know that it was due in great measure to the work of Wallace West of the Press Department … if radio drama grew up a little through my efforts in the last year, I believe that radio publicity grew up equally as much through the efforts of your own Wallace West …35

Oboler even credited West with the idea for “Profits Unlimited”, fittingly enough, a parable of corporate myopia36.

In his letter to Oboler, West went on to explain that:

… [W]e’ve had a lot of difficulty in the past with the Blackett-Sample-Hummert agency. They insist on approving every line of copy that goes out on one of their shows … Under the circumstances it rather looks to me as if you should try to get the agency to hire a man who knows your ideas and technique to write your publicity which will then, of course, be released by NBC through its usual channels. Perhaps you can work out some other arrangement with them and NBC. For the present we’re stymied, for no one here wants another run-in with B.S.H.37

Oboler was not about to lose West’s ace publicity write-ups. It took nearly a month for him to move the needle on BSH’s intransigence regarding publicity, “… Dear Wally: The enclosed letter to [William] Kostka38 is self-explanatory; this is your official carte blanche to release any publicity which may come your way regarding the fall series. It’s to be known as ‘Everyman’s Theatre, Written and Directed by Arch Oboler.’ … I know you’ll do a job …”39 By late September, Wally West had some good news for Oboler:

… The first thing I have to report is that I had a long phone conversation with [Larry] Milligan of the BSH office and he is stepping out of the picture so far as publicity is concerned so I no longer will have to send my material to him for approval but can work directly with you … The second thing is that Kostka wants to give Everyman’s Theater the biggest possible buildup …40

For the moment, it seemed that Oboler had won the battle for absolute complete freedom of publicity as well as creative control. But, with the very first play for his new series, an abbreviated repeat of his radio drama, “This Lonely Heart”, starring Alla Nazimova, things started to go awry:

The broadcast was on a Friday; on Wednesday … Variety … reviewed the opening show with type that was dipped in corrosive sublimate … in spite of the fact that the gentlemen of the soap agency [BSH] had apparently approved of the initial broadcast of their new series, the appearance of that venomous review made them doubt their own ears and immediately began an attitude of suspicion which colored the rest of the series … The doubt incubated in the soap men by the trade-paper review was not dispelled by the events preceding the second broadcast of the Everyman’s Theatre series.41

As was becoming the pattern with each battle for control of Everyman’s Theater, with the second broadcast, Oboler started from a place of optimism and excitement:

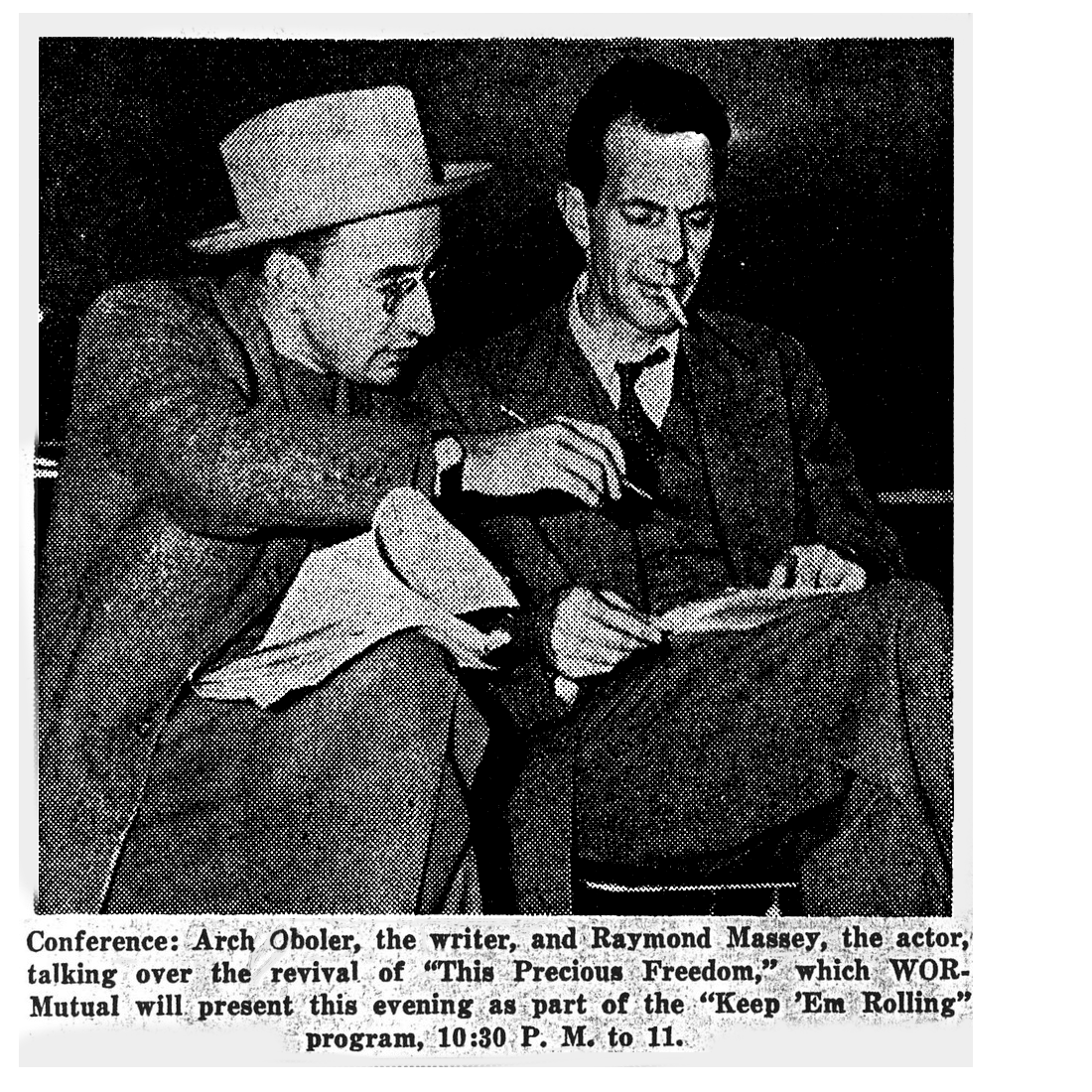

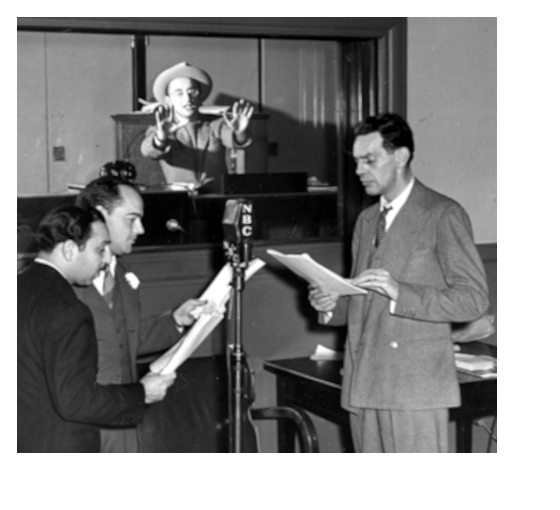

… First, Wally, here’s the stuff on the second play which I will do … the contents of which I am going to keep secret other than to say that it’s an exciting melodrama about these days we live in. In fact, before the play begins I will come on the air and say these words: “This is the story of a tomorrow which should never happen.” … I talked the play over with [Raymond] Massey42 when he was up at the Warner Bros. Ranch … he was playing the part of John Brown43 , and so help me, we talked over the play between the takes where he climbs the gallows to be hanged. Massey was just a little doubtful whether or not I could compress the subject matter into half an hour; I airmailed the script to him a few days ago and he wired back “Your play beyond praise. My grateful thanks.” And with that, Wally, I close this episode and leave the rest to you.44

But the episode was hardly closed due to the play’s controversial content. Arch Oboler’s “This Precious Freedom”45 tells the story, not of John Brown, but John Stevenson (Raymond Massey), a successful American businessman who, upon returning from vacation to his hometown, discovers that it is occupied by a fascist fifth column. Oboler does not name the traitors, but the German accent of the chief villain leaves no mistake as to their Nazi affiliation. Now an enemy of the state, Stevenson is interrogated and tortured. At the bleak finale, he acknowledges his complicity with the enemy:

Voices (whispering fast): Don’t antagonize them! We’ll have to do business with them! Let them talk! Mind our own business! Don’t antagonize them! (Etc., fading.)

John [Stevenson]: Yes — all the things I said! 46

As with the film Escape (1940), Oboler launched a more direct attack against the Nazi regime with his radio play. But the powers that be were not about to let “This Precious Freedom” escape onto the airwaves:

I was immediately in boiling water again; the network took one quick look at the script and announced it could not be broadcast. Why? We were not at war with Nazi Germany. I insisted that every decent human being in the world was at war with Nazi Germany. The traffic in teletypes and long-distance phone calls became titanic. The final word from all the vice-presidents-in-charge was that the play could not be broadcast …

Raymond Massey … was so infuriated at the situation that he joined me in a cross-country flight to Radio City. On our arrival, we remonstrated, we threatened, we reasoned, we cajoled. Finally I made the flat statement that unless This Precious Freedom was broadcast as written, I would withdraw the program from the air, making it the shortest-lived commercial series in radio history. The cancellation of a single play was of small concern to the network the potential loss of six or seven hundred thousand dollars of network time was another kettle of kilocycle fish …47

We have only Arch Oboler’s account of the brouhaha over “This Precious Freedom”. Given that this broadcast was so controversial and given how well documented Everyman’s Theatre is in the Arch Oboler Collection at the Library of Congress, it’s very surprising that there are no letters or telegrams about this quarrel in that collection. Therefore, we have to glean the perspectives of NBC, Procter and Gamble, and BSH given what we know about these organizations’ attitudes at the time.

At Radio City’s offices presided NBC’s most powerful executive, David Sarnoff. Similar to Oboler, Sarnoff was the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants. He ascended to the presidency of both RCA and NBC, suffering many antisemitic indignities. He was appalled by the Nazis and apprehensive about their aims but “sensitive to the antisemitic charges that Jews controlled the media and that World War II was a ‘Jewish war[.]'”48 Sarnoff believed that he could best combat Nazism by developing communication technologies that America would need should it become involved in World War II. In his essay, “Why Sarnoff Slept”, David Weinstein notes that “[d]ramatists like Archibald MacLeish, Orson Welles, and Arch Oboler used thinly veiled allegories to warn of the dangers of fascism, although, before December 7, 1941, network bans on ‘propaganda’ precluded them from opposing Nazism more explicitly.”49 For NBC, Oboler’s “This Precious Freedom” may have been too explicitly anti-Nazi and also received as an attack on the business community for its complicity of silence. In fact, that was how it was intended:

… [D]uring the years when you could have spoken to the people, during the years when you were saying that Spain was not to our interest, that Ethiopia was not to our interest, that the cries of the tortured in Manchukuo and the Third Reich were not to our interest, you were digging the grave of your own security … The network thought the play [“This Precious Freedom”] was “dangerous,” that it might “arouse” the listening public.

… that is what both Mr. Massey and I wanted above all else …50

As far as the attitudes of Procter & Gamble and Blackett-Sample and Hummert are concerned, we have to engage in a bit of informed conjecture. As we read in part one of this article, Oboler did not lay blame at the feet of his commercial sponsor, P. & G.51 By late 1940, P. & G. was secretly involved with arming Great Britain against the Nazis, “… U.S. Army personnel approached P&G about building and running an ordnance plant, to load propellant charges into shells. The company responded, setting up a plant in Tennessee, then another in Mississippi …”52 It is highly likely, however, that P. & G. would have officially deferred to NBC’s policy of neutrality regarding Nazi Germany. Like NBC, it appears that P. & G. unofficially supported anti-Nazi efforts through the development of technology. Instead of targeting P. & G., Oboler blamed the contact man from BSH53 , and it is possible that P. & G.—the maker of soap products—allowed its advertising agency to do its dirty work for them. Hill Blackett of BSH was certainly not neutral regarding politics as he “played a major part in running the 1936 U.S. presidential campaign of the Republican candidate Alf Landon54 , who was defeated in the landslide victory of the incumbent Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt.”55 Therefore, it’s reasonable to conclude that BSH maintained an isolationist position regarding Nazi Germany.

The attitudes of silence and official neutrality that Arch Oboler encountered made “This Precious Freedom” far more realistic and immediate than his obliquely anti-fascist plays for Lights Out. Oboler’s radio drama imagines a frightening and credible fascist America, a place where human rights are non-existent. Oboler’s “exciting melodrama about these days we live in” was responding to two movements in American politics—the German American Bund and The America First Committee. The America First Committee was founded in 1940, it was funded by prominent business leaders of Oboler’s hometown Chicago, and it was a coalition between left and right.56 In fact, Oboler’s new friend, Frank Lloyd Wright, was a member of America First, one of the largest peace organizations in U.S. history.57 Oboler and Wright passionately disagreed about the threat posed by fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, with Wright chastising Oboler as a “warmonger”, “… Knowing you are steeped in pro-war propaganda I am taking the liberty of sending you (regularly) the Scribners Commentator58 and The Herald59. I do this imagining that you want to know what is going on in the minds of your opponents now about 89% of the U.S.A …”60

This quarrel over American isolationism unfolded while Wright was building Oboler’s dream house, which to the author was also a symbol of his individuality and belief in personal freedom. Oboler’s friendship with Wright spanned twenty years, nevertheless, their relationship was often fraught when it came to politics. In a series of unpublished notes on Oboler’s memories of Wright, Oboler recounts the following ugly and confusing scene at Taliesen West61 :

It was an amphitheater of a room … Wright was talking to a few handfuls of very attentive student apprentices.

When I came into the place he greeted me with “Surprised to see you. Thought you’d be busy with your propaganda broadcasts.”

‘Propaganda’? Only a few weeks before he had commended me on a play I had written for Raymond Massey about a business-man who returns from a hunting trip to find his familiar world iron-gripped in a Fascist takeover62 . Mr. Wright’s next words: “It looks as if you Jews are going to get the war you want, doesn’t it?”

Every young back in the place stiffened. All eyes were centered on me. I took a deep breath. In the months that I had known him there had never been even a touch of racism on Mr. Wright’s part. Why this? …

… In the silence of the room. I found voice. I said that World War II, if it came, would hardly be a Jewish affair; it would be the consequence of multi pressures, including the revulsion of free men against the horrors of Naziism, this anti-human attempt to force civilization to lose its small, hard won climb out of the slime.

I left Taliesen, that day, heartsick that this artist who blended man and beauty, when it came to architecture, could possibly be so blind to the realities of history …63

A letter from Oboler to Wright on August 10, 1947, demonstrates that Frank Lloyd Wright’s attitudes were little changed immediately after World War II:

Dear Frank: … One little phrase in [your letter] cannot pass unchallenged — “Palestine Palms”.

If there were six million dogs (note I am not saying six hundred or six thousand, or even six hundred thousand – I am saying six million) who were murdered, I am sure you would have a sense of overwhelming pity and would do nothing, not even by inference, that would tend to make more unhappy the plight of the few remaining dogs in the world …

No, Frank, you’re much too big a person to indulge in small anti-Semitics!

Cordially, Arch Oboler. 64

Wright’s note in response reads as socially inept and is hardly exculpatory:

Dear Arch: No anti-Semitics on my part, I swear. You got that way once before! Remember? All wrong!

I just feel now as I felt then there should be no racial clique in our “free” country and I for one don’t like to see too many of one kind in one place.

Hence the mischief “Palestine Palms”.

The Jews, the Irish and the Welsh should stick together though. All the bankers, all the police, all the prime ministers … What else?

Affection, Frank Lloyd Wright65

The isolationism and patrician anti-Semitism typified by his friend, Wright66 , was bad enough, but Oboler was even more alarmed by the German American Bund. The Bund, the most powerful pro-Nazi organization in the United States, had held an enormous rally in Madison Square Garden on February 20, 1939.67 Oboler wrote “This Precious Freedom” to warn Americans of the unique threat to life and liberty posed by Hitler and Nazi Germany. Ultimately, the NBC Red Network broadcast Oboler’s “This Precious Freedom” as scheduled on October 11, 1940 at 9:30PM EST, “… [t]he play was given the only citation awarded any commercial program by the Institute [for Education by] Radio meeting at Ohio University … In making the award, the judges … stated: ‘… The author is one of radio’s writers who is fighting the good fight for democracy steadily, wherever he can …'”68 Oboler’s radio play was also acknowledged by major radio critics such as Bob Stephan69 , who wrote Arch Oboler the following: “… The best program from my front seat at the radio set you’ve done in the new series brought Raymond Massey in ‘This Precious Freedom.’ … My best to a lucky guy who can work out of New York, Chicago and Hollywood as he darn well pleases.”70 Unfortunately, Bob Stephan’s view of Oboler’s freedom turned out to be naive, and Everyman’s Theatre made its final broadcast on March 28, 1941:

I received notice that the first thirteen weeks of the series had gone by and that I was being renewed, and the shock of this renewal had hardly worn off when I was told that henceforward the plays would be interrupted for a middle commercial … I protested, shall we say, vigorously. I was told that the sponsor felt that he was entitled to a sales spiel for his soap powder at the beginning of his program, at the middle of his program, and at the end of his program. The decision had been made. It was either or.

It was or …71

After Everyman’s Theatre, there was mostly “great blank silence” until a deafening blast of irony and catastrophe sounded in the form of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941—Arch Oboler’s birthday. Suddenly, Oboler’s “propaganda” was in great demand. He must have felt completely vindicated when General Motors, a company that symbolized the businessmen he criticized, approached him to film “This Precious Freedom” in the spring of 1942:

A vice president of General Motors came to me. He had heard “This Precious Freedom” on the air, and he said that he would like me to make a motion picture, with any money that I wanted to spend on it—get a star and a full Hollywood cast and crew … It wasn’t made for theatrical purposes, just for the workers—to make them realize that there was a war coming, and the dangers of not producing.72

GM put up the money and, to produce the film, Oboler contracted with that company’s partner, Sound Masters Incorporated, a New York based industrial film company. Larry Corcoran of GM’s Public Relations Department in New York gave Sound Masters a letter of authority for Oboler to direct the film. Corcoran’s letter of authority explains how GM intended to use the picture:

We propose to use this picture as part of our Employee Morale Program—showing it in rented theaters and auditoriums in or near plant cities, at meetings in cities where we have General Motors Clubs, and to make it available for non-theatrical distribution, in accordance with our usual custom. Such distribution includes schools, clubs, churches, army camps, etc. In no case is admission to be charged in connection with any of the foregoing distribution, with the possible exception of isolated cases in which shows are put on for charitable purposes.73

To familiarize him with GM’s industrial film template, Oboler received a sixteen-millimeter print of a film which Sound Masters produced for that company, What So Proudly We Hail (1940). Oboler must have thought that he could easily surpass this uninspired little short and its perfunctory promotion of democracy, capitalism, and America as the “last outpost of freedom” in the world. Indeed, he did surpass the film:

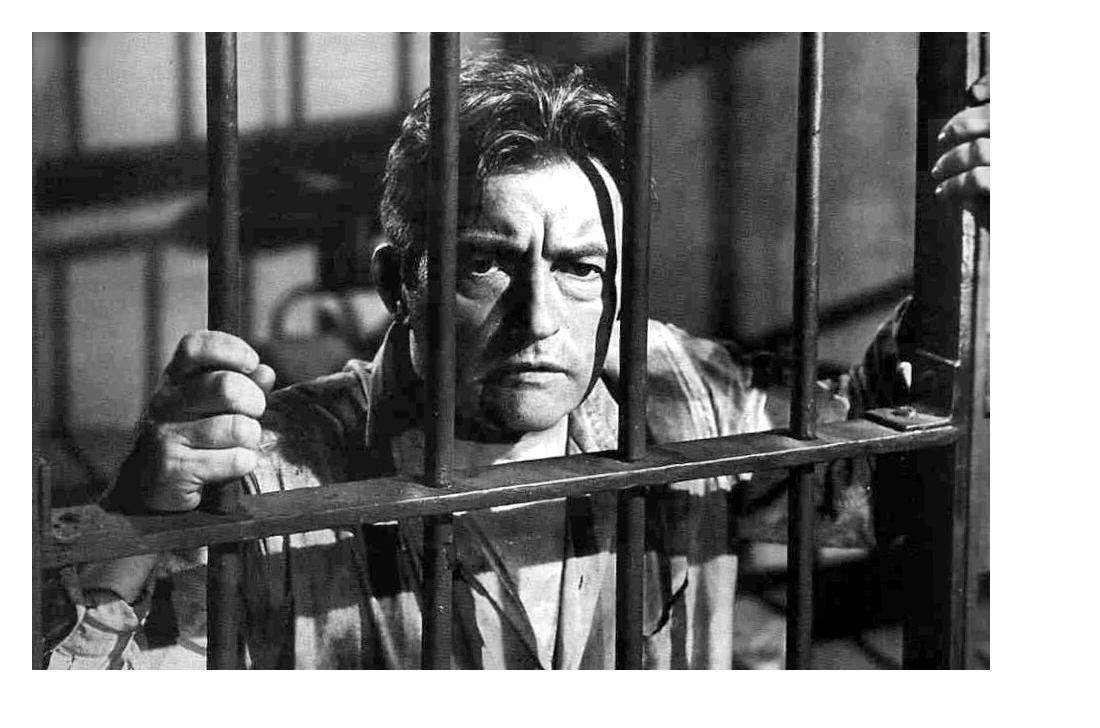

I got Claude Rains as the star, and as the photographer, I had Robert Surtees, who became a winner of Academy Awards, doing his first picture as a first cameraman. We had a lot of creative folks making the picture, and I did all sorts of things, camera-wise, such as subjective effects of a man losing his freedom in his own house. This was America being taken over by a Nazi group, not German, but simply people who believed in the fascist ideal74.

Oboler’s memory is somewhat flawed regarding the Nazi group not being German. Although some of the henchmen in Oboler’s film are clearly American, their leader, as portrayed by Martin Kosleck75 (The Examiner), is quite clearly a Nazi German. In the film, Oboler has Kosleck fidget with a desk-toy that is a pinwheel in the shape of a Nazi swastika, mounted on a trapezoid that is decorated with the rising sun of Imperial Japan. Like the eponymous radio play, This Precious Freedom (1942) implies that small town America has been captured by the German American Bund with material support from Nazi Germany. Oboler’s This Precious Freedom (1942) is no traditional industrial film, it is shockingly violent for its time and avant-garde. For example, Claude Rains’s character is subjected to extended scenes of torture, and Oboler saturates his film with radio montage techniques:

Without warning, the Examiner slaps Stevenson viciously across the mouth, then he carefully takes out a breast-pocket handkerchief and wipes the hand he had used …

Examiner ( voice over scene): Surely you have heard of the plan, Mr. Stevenson! – the great plan! His plan.

The swastika on the desk dissolves into a swastika-emblazoned copy of the book “MEIN KAMPF by Adolph Hitler”.

Examiner: The novel plan!

We hold on the book – behind it rises fire – the book DISSOLVES TO the ranting mouth of a Nazi propagandist – the mouth jaws wordlessly away – it fills the screen. Over the scene we hear:

Examiner: Always it was there, and always we followed it! We poured our propaganda in on you – yes, we used your own weaknesses against you!

The mouth has now split up into a number of mouths which fill the frame; over the scene we hear:

Examiner: We hid behind many faces as we spoke, as we whispered!

Now, alongside each mouth, there is a listening ear.

Examiner: And what did we say, Stevenson? Remember!

The mouths with their attendant ears are now criss crossing on the screen – a small ear with the whispering mouth next to it moves forward until it fills the screen, then dissolves, and another comes from another angle, and another and another, continuing to criss-cross, as, on the soundtrack we hear:

Voices: Why work too hard? The war will be over soon! Why work too hard? The big bosses are getting it all! Why work too hard? Labor is getting it all! Why work too hard? It is a phony war! Why work too hard? Germany’s breaking up from within! Why work too hard? The war is practically over! Why work too hard? It’s England’s war! Why work too hard? It’s Russia’s war! Why work too hard? It’s China’s war! Why work too hard? Why work too hard? Why work too hard?

The mouths and the ears begin to swirl in a spinning whirlpool as, on the sound track we hear the Examiner’s voice:

Examiner: Confusion, Stevenson! How we gave you confusion! But we were not confused, Stevenson! Always there was the plan! The plan!

The swirling has stopped and once more we see the book “Mein Kampf by Adolph Hitler”.

Examiner: So when the final test came we were one people – our army and our workers one people, united behind his great plan – and you, you had nothing but confusion!

Fire has begun to rise behind the book – now, suddenly, blood begins to pour from between its pages, and in this horrible stream we see an upflung arm, and then a head, and then a leg – the bodies of the defeated.

Examiner: So now we have won, Stevenson! With the aid of our Japanese brothers who will crush you from the West while we smash you from this Eastern foothold we have won76! You hear me – won! And you have no rights, Stevenson!

The swastika-book dissolves quickly into the stationary swastika on the desk – the camera is shooting through the swastika across the desk so that we see the Examiner’s inflamed face as he shouts:

Examiner: No rights, Stevenson! No one has the right but we who are the leaders! Leaders of the blood! This is our America!77

Unfortunately, the public never saw Oboler’s original film version of This Precious Freedom (1942). When the US was isolationist, NBC failed to withhold the radio play from the public, but when the US was at war, General Motors successfully suppressed the film version of the radio play that it hired Oboler to create. The irony is absurd:

When it was finished and in the can, suddenly General Motors announced that they were not going to show it to their workers. It cost the advertising head his job [Larry Corcoran] for having promoted it—he was fired very quietly78. Why, you want to know? Because General Motors was doing business with Germany and they didn’t want to hurt that business, even if it was only going to last two or three more months.79

Oboler’s accusation against General Motors is incorrect. Oboler was hired to make This Precious Freedom in 1942, when the United States was at war with Nazi Germany. Oboler’s accusation seems to imply that GM was doing business with Nazi Germany after it declared war on the United States; confusingly, it also seems to imply that GM was wrapping up business with Nazi Germany before the Axis power declared war on the United States. While it is true that GM, through its German subsidiary Adam Opel, A.G., helped rearm Nazi Germany before it declared war on the United States, no evidence has surfaced to substantiate accusations that GM continued to do business with an enemy country.80 Despite an extensive search of Arch Oboler’s enormous file on the film, I am unable to definitively uncover GM’s true motivation for shelving Oboler’s picture. However, Oboler’s papers do offer some interesting possibilities.

On December 7, 1942, Arch Oboler sent a telegram to Claude Rains, opining that GM’s “OBVIOUS REASON” for shelving This Precious Freedom (1942) was that it was “TOO STRONG MEAT.”81 However, this brings up the question of why GM felt that Oboler’s film was “too strong meat.” On July 13, 1943, The Film Daily of New York City reported that GM shelved the film “… because the company considered it ‘inflammatory’.”82 The question is still ‘why was the film inflammatory’? GM was familiar with the radio play, presumably someone at GM had approved the script. Perhaps they simply got cold feet when they saw how violent Oboler’s film was:

General Motors sold the picture to some Hollywood entrepreneurs, who released the picture after the war, and by then the Nazi theme was dated. [The film was released as Strange Holiday, 1946 83]. They tried to cut the picture so that it looked like an anti-Soviet thing. I had nothing to do with it, but to me it typified the business as usual of the big corporation.84

Contrary to his remembrance, Oboler was involved in the sale of the film because he desperately wanted people to see it. On December 7, 1942, Arch Oboler sent a telegram to Claude Rains85 asking him, “… IF YOU ARE WITH ME IN FORCING GENERAL MOTORS TO SHOW PICTURE OR ELSE PERMIT US TO SELL IT … TIME IS WASTING AND PICTURE MUST BE RELEASED NOW OR NOT AT ALL86… ”

Oboler’s picture was not “released now”, but it was released “at all.” The series of transactions that mutated Oboler’s timely film This Precious Freedom (1942) into an untimely Franken-film called Strange Holiday (1945) is tortured and byzantine. In the summer of 1943, MGM, the studio that hired Arch Oboler to write Escape, purchased This Precious Freedom.87 On July 1, 1943, Oboler wrote to Eddie Mannix88 , “I was pleased to hear that you had bought “This Precious Freedom” and want to offer my services in any way possible.”89 Unfortunately, MGM did not want Oboler’s services; instead, they wanted to cut the picture up for stock shots in one of their two-reelers.90 That was unacceptable to Oboler who was an easy man to frustrate but a hard man to discourage. A former intrepid salesman, he would have approached entrepreneurs to persuade them to redeem This Precious Freedom from MGM, expand it, and sell it as a feature with the marquee value of Claude Rains. On December 27, 1943, MGM91 sold Oboler’s film to bargain basement producers A.W. Hackel92 and Edward F. Finney93 . On March 21, 1944, Hackel, Finney, and now Max M. King94 contracted with Oboler to write the script for reshoots of This Precious Freedom,95 which was now to be called Terror on Main Street:

… The way to make the motion picture timely is to change the time element to a post-war theme … A major change that I would make would be with Martin Kosleck [the Examiner]. I would reshoot him and give him new dialogue; the essences of it would be that although people like [John] Stevenson thought that Germany, having lost the war, was defeated — nevertheless she was not. Because always there were elements in America … who hid behind the words “Americanism” and used democratic freedoms for their own evil purposes. In other words … this would be a revolution from within lead by fascist-inspired leaders. This dialogue change would occur behind the montage also emphasizing the post-war possibilities of fascism unless people guard against the rise of native power-mad individualists …96

In the jail scene when John Stevenson thinks about what has happened in the world – we could show quick flashes of long lines of slave labor, the sanctity of home being violated, lynchings, concentration camps … universities and schools with signs “Closed until further notice” and other cuts indicating the ruthless and terrible destruction of all civilization by the new fascist over-lords.97

Oboler’s film was finally released in New York by Mike J. Levenson and Elite Pictures Corp98, in October 1945, as Strange Holiday. In October 1946, the following year, Strange Holiday went into wider release through Producers Releasing Corporation99. Oboler and his partners sold the film yet again to M&A Alexander Productions100, and this is the version that he claims was recut as an anti-Soviet picture and retitled, The Day After Tomorrow (1952).101 Despite Oboler’s claim that he had nothing to do with this film version, in his film collection at the Library of Congress102 , I found several reels of film elements pertaining to this version. Further, in the collection of Oboler’s papers, there is an itemized statement of expenditures on The Day After Tomorrow, which reveals Oboler’s involvement.103 Oboler was certainly anti-Soviet and anti-communist, he was also however, anti-McCarthy. The Day After Tomorrow sounds like a film version of Oboler’s This Precious Freedom that would be informed by McCarthyite hysteria. Therefore, it’s possible that Oboler sought to distance himself from this version, having been, himself, victimized by McCarthyism.

Unlike his radio play “This Precious Freedom”, there was no acclaim for Oboler’s transmuted film version, Strange Holiday (1945). The New York Times, which had so glowingly reviewed Escape (1940), found Strange Holiday to be little more than a shocking account of brutality and inhumanity directed against helpless beings:

One of the most curious anti-Nazi films yet to reach the screen …”Strange Holiday” is … a prophecy of fascism to come in America … Mr. Oboler has a provocative thought there but in dramatizing it he has gone off on a melodramatic tangent … Such a theme is fraught with dramatic possibilities, but Mr. Oboler has frittered it through a succession of sadistic sequences which smack of having been contrived for their shock effect … A cast of good players, headed by Claude Rains, aren’t able to do much toward making this film comprehensible, for, in his direction, Mr. Oboler permits the story to ramble and his propensity for abruptly cutting sequences is confusing, rather than artistic …104

As the review suggests, Oboler’s message was worthwhile, but as a film, Strange Holiday was a shambolic propaganda palimpsest. In 1946, the year of Strange Holiday‘s wider release, Oboler dictated a cogent and trenchant letter directed at Ohio Congressman, Frederick C. Smith. Oboler’s letter castigated Smith for his “outrageous statement”, on a radio appearance, where the Congressman opined that “if not for certain machinations of President Roosevelt”105 the US would not have entered World War II. In his letter to Smith, Oboler wrote, “surely you must know, had we not entered the last war, the gas chambers would be in operation at this moment in the United States . . . “106 Clearly, this Ohio Congressman had not been one of the judges of Oboler’s radio play “This Precious Freedom” at the Ohio State University meeting of the Institute for Education by Radio. Congressman Smith’s outrageous claims vindicated, at least, the thesis of Strange Holiday and demonstrated for Oboler that the threat of a fascist America was undiminished and remained “a tomorrow which should never happen.”

In the next installment, Oboler makes two films for MGM, and the Golden Age of Radio comes to a close.

End Notes:

1 See https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2024/10/halloween-heartthrob-the-chicken-heart-that-gobbled-up-the-globe/

2 Ethel Vance was the pseudonym of Grace Zaring Stone. Stone wrote her novel Escape (1939) under a pseudonym to avoid imperiling her daughter, who was living in occupied Europe. Among other novels, Stone also wrote The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1930).

3 The film co-credits the screenplay to Marguerite “Maggie” Roberts, who later wrote the screenplay for True Grit (1969).

4 Arch Oboler to Lewis Titterton. April 9, 1940. Box 4, Folder 1. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

5 On Arch Oboler’s Plays, Oboler wrote anti-Nazi stories such as “The Ivory Tower” (starring Alla Nazimova). However, they were still oblique enough to avoid clashes with the official neutrality policies of NBC.

6 Bell, Douglas. “Arch Oboler, Chicago and New York:1907-1941” Five Directors: The Golden Years of Radio. Edited by Ira Skutch. Lanham, MD. Scarecrow Press. (1998), p. 151

7 “Dad hated rewrites.” Steve Oboler, interview by author, Denver, July 5, 2025.

8 Oboler to Lewis Titterton. August 22, 1940. Box 4, Folder 1. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

9 Crowther, Bosley. ” ‘Escape,’ an Exciting Film Version of the Ethel Vance Novel.” The New York Times. November 1, 1940. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/1940/11/01/archives/the-screen-escape-an-exciting-film-version-of-the-ethel-vance-novel.html

10 Arch Oboler to Leo Mishkin. November 6, 1940. Box 4, Folder 6. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

11 Bell, Douglas. “Arch Oboler, Chicago and New York:1907-1941” Five Directors: The Golden Years of Radio. Edited by Ira Skutch. Lanham, MD. Scarecrow Press. (1998), p. 151

12 Oboler, Arch. Escape. June 3, 1940. Unpublished. Box 300, Folder 9. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

13 Arch Oboler to Leo Mishkin. November 6, 1940. Box 4, Folder 6. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

14 Arch Oboler to Maxine Block. October 31, 1940. Box 4, Folder 6. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

15 “An Oboler Omnibus, Part II.” Same Time, Same Station, KRLA, Pasadena. April 23, 1972. Radio

16 The contact man was likely Larry Milligan.

17 Until 1942, NBC was divided into two networks. The so called “NBC Blue” and “NBC Red” networks.

18 Arch Oboler to Lewis Titterton. June 6, 1940. Box 4, Folder 1. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

19 Arch Oboler was represented by the William Morris Agency.

20 Lewis Titterton to Arch Oboler. June 6, 1940. Box 4, Folder1. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

21 Lewis Titterton to Arch Oboler. June 11, 1940. Box 4 Folder1. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

22 Soap manufacturers Procter & Gamble spent millions of dollars advertising on radio. “In 1932 Procter & Gamble introduced the radio audience to ‘The Puddle Family,’ the first ‘soap opera,’ so called because of the sponsor.” See https://www.britannica.com/money/Procter-and-Gamble-Company. Arch Oboler loathed soap operas.

23 Lewis Titterton to Arch Oboler. June 6, 1940. Box 4, Folder1. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

24 Arch Oboler to Lewis Titterton. June 13, 1940. Box 4, Folder 1. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

25 Id.

26 The final broadcast of Arch Oboler’s Plays was a rebroadcast of Oboler’s play “The Ivory Tower”, March 23, 1940.

27 Arch Oboler to Lewis Titterton. June 13, 1940. Box 4, Folder 1. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

28 Id.

29 Jimmy Parks was a friend of Oboler’s from his Chicago days. Parks worked for an entertainment agency called The General Amusement Corporation (GAC). Parks arranged for Oboler to fly to Chicago to sell BSH a commercial version of Arch Oboler’s Plays. As he had done for Lewis Titterton, Oboler played recordings of his plays for BSH’s contact man Larry Milligan. According to Oboler, he and Parks made the sale on the spot. See Arch Oboler to Lewis Titterton. June 13, 1940. Box 4, Folder 1. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

30 Oboler, Arch. Oboler Omnibus: Radio Plays and Personalities. New York. Duell, Sloan & Pearce. (1945), p. 155

31 “Profits Unlimited” Arch Oboler’s Plays, NBC. October 28, 1939. Radio.

32 Oboler, Arch. Oboler Omnibus: Radio Plays and Personalities. New York. Duell, Sloan & Pearce. (1945), p. 155

33 Roughly $92,000 in 2025.

34 Wallace West to Arch Oboler. July 10, 1940. Box 4, Folder 2. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

35 Arch Oboler to John Royal. April 11, 1940. Box 4, Folder 1. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

36 “Profits Unlimited was based on a suggestion by Wallace West. I hope, that the social drama can also be entertaining.” Oboler, Arch. Fourteen Radio Plays by Arch Oboler. New York. Random House. (1940), p. 216

37 Wallace West to Arch Oboler. July 10, 1940. Box 4, Folder 2. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

38 William Kostka was the head of NBC’s publicity department in NYC.

39 Arch Oboler to Wallace West. August 5, 1940. Box 4, Folder 2. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

40 Wallace West to Arch Oboler. September 23, 1940. Box 4, Folder 2. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

41 Oboler, Arch. Oboler Omnibus: Radio Plays and Personalities. New York. Duell, Sloan & Pearce. (1945), p. 156-157

42 Raymond Massey was Canadian. Canada entered World War II on September 10, 1939.

43 The film was Santa Fe Trail (1940)

44 Arch Oboler to Wallace West. October 1, 1940. Box 4, Folder 2. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

45 The radio play “This Precious Freedom”, which stars Raymond Massey, is entirely different from an earlier radio play by Arch Oboler, which is also titled “This Precious Freedom”. The earlier radio play is about a machinist who loses his livelihood and family. In a card index of copyrights, Oboler designated the earlier radio play as “This Precious Freedom [Plot #1]”, and the later radio play, starring Raymond Massey, as “This Precious Freedom (Bill of Rights) [Plot #2]”. See Card index of Oboler’s radio series and episodes. Box 363. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress. “This Precious Freedom [Plot #1]” is published in Fourteen Radio Plays by Arch Oboler. “This Precious Freedom (Bill of Rights) [Plot #2] is published in This Freedom: Thirteen New Radio Plays by Arch Oboler and Oboler Omnibus: Radio Plays and Personalities.

46 Oboler, Arch. Oboler Omnibus: Radio Plays and Personalities. New York. Duell, Sloan & Pearce. (1945), p. 174

47 Id, pgs. 157-158

48 Weinstein, David. 2007. “Why Sarnoff Slept: NBC and the Holocaust.” In NBC: America’s Network, edited by Michele Hilmes, p. 109. Berkeley: University of California Press.

49 Id at p. 105

50 Oboler, Arch. This Freedom: Thirteen New Radio Plays by Arch Oboler. New York. Random House. (1942), p. 218

51 “An Oboler Omnibus, Part II.” Same Time, Same Station, KRLA, Pasadena. April 23, 1972. Radio

52 Dyer, D., Dalzell, F., Olegario. R. Rising Tide: Lessons from 165 Years of Brand Building at Procter & 52

Gamble. Boston. Harvard Business Review Press. p. 64

53 “An Oboler Omnibus, Part II.” Same Time, Same Station, KRLA, Pasadena. April 23, 1972. Radio

54 It is notable, however, that in a speech on radio, Alf Landon “expressed outrage at Germany’s brutality.” Weinstein, David. 2007. “Why Sarnoff Slept: NBC and the Holocaust.” In NBC: America’s Network, edited by Michele Hilmes, p. 100. Berkeley: University of California Press.

55 Kirtley, Al. “Blacketts in politics.” The Blacketts of North East England. November 21, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.theblacketts.com/node/67

56 Simon, Scott. ” ‘America First,’ Invoked By Trump, Has A Complicated History.” NPR.org. July 23, 2016. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2016/07/23/487097111/america-first-invoked-by-trump-has-a-complicated-history

57 Id.

58 Apparently, Frank Lloyd Wright was not as immune to propaganda as he may have supposed. “Scribner’s Commentator … ceased publication in 1942 after one of the magazine’s staff pleaded guilty to taking payoffs from the Japanese government, in return for publishing propaganda promoting United States isolationism.” “Scribner’s Magazine.” Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scribner%27s_Magazine

59 “The Herald was an isolationist newspaper published in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. Scribner’s Commentator was a sister publication from the same city. Scribner’s Commentator’s editor, Ralph Townsend was eventually imprisoned for being an unregistered foreign agent for the Japanese government … The Herald was bankrolled by $38,000 in cash [by] publisher, Douglas MacCollum Stewart … Baron von Strempel, a Nazi agent, testified in court that he had bankrolled Stewart with $15,000. Stewart was jailed for 75 days in a sedition trial for obstruction of justice.” “Herald Combined Files.” Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/herald-combined-files

60 Frank Lloyd Wright to Arch Oboler. September 22, 1941. O014. Getty Center, Los Angeles. Wright, Frank Lloyd. Frank Lloyd Wright correspondence, 1900-1959, 1900.

61 Taliesen West was Wright’s famous Arizona compound.

62 Perhaps, like left-wing Sinclair Lewis, who was a member of America First, Wright feared a homegrown fascist America unrelated to Nazism and international conflict. Lewis had authored the dystopian novel It Can’t Happen Here (1935), about homegrown American Fascism. Still, with its depiction of a Nazi takeover of America, it is puzzling that Wright would have approved of Oboler’s “This Precious Freedom”.

63 Oboler, Arch. “Wright Memories”. Unpublished. Box 137, Folder 11. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

64 Arch Oboler to Frank Lloyd Wright. August 10, 1947. O032. Getty Center, Los Angeles. Wright, Frank Lloyd. Frank Lloyd Wright correspondence, 1900-1959, 1900.

65 Frank Lloyd Wright to Arch Oboler. August 14, 1947. O032. Getty Center, Los Angeles. Wright, Frank Lloyd. Frank Lloyd Wright correspondence, 1900-1959, 1900.

66 At some point, Frank Lloyd Wright must have “forgiven the Jews” for World War II and the Holocaust because he built the Synagogue Beth Shalom (House of Peace) in the 1950s.

67 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “The German American Bund: A Pro-Nazi Organization in the United States”. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved from https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/german-american-bund on July 12, 2025.

68 Oboler, Arch. This Freedom: Thirteen New Radio Plays by Arch Oboler. New York. Random House. (1942), p. 218

69 Halper, Dona L. Stephan, Robert Studebaker. Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Retrieved from https://case.edu/ech/articles/s/stephan-robert-studebaker

70 Bob Stephan to Arch Oboler. Undated. Box 4, Folder 6. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

71 Oboler, Arch. Oboler Omnibus: Radio Plays and Personalities. New York. Duell, Sloan & Pearce. (1945), p. 179

72 Bell, Douglas. “Arch Oboler, Chicago and New York:1907-1941” Five Directors: The Golden Years of Radio. Edited by Ira Skutch. Lanham, MD. Scarecrow Press. (1998), p. 145

73 Larry Corcoran to Sound Masters, Inc. July 23, 1942. Box 174, Folder 3. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

74 Bell, Douglas. “Arch Oboler, Chicago and New York:1907-1941” Five Directors: The Golden Years of Radio. Edited by Ira Skutch. Lanham, MD. Scarecrow Press. (1998), p. 145

75 Kosleck had played Joseph Goebbels in Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939).

76 Oboler’s film presages Philip K. Dick’s novel The Man in the High Castle (1962) and the television series (2015-2019).

77 Oboler, Arch. This Precious Freedom, Final Revision. July 15, 1942. Unpublished. Box 349, Folder 3. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

78 See Edward Finney to Arch Oboler. March 28, 1945. Box 5, Folder 3. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

79 Bell, Douglas. “Arch Oboler, Chicago and New York:1907-1941” Five Directors: The Golden Years of Radio. Edited by Ira Skutch. Lanham, MD. Scarecrow Press. (1998), p. 145

80 See Turner, Henry Ashby Jr.. General Motor’s and the Nazis: The Struggle for Control of Opel, Europe’s Biggest Carmaker. New Haven. Yale University Press. (2005).

81 Arch Oboler to Claude Raines. December 7, 1942. Box 15, Folder 5. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

82. “Oboler GM Footage to Metro as Stock Shots” The Film Daily. July 13, 1943. p. 20

83 Strange Holiday was given a limited release in 1945 and a wide release in 1946.

84 Bell, Douglas. “Arch Oboler, Chicago and New York:1907-1941” Five Directors: The Golden Years of Radio. Edited by Ira Skutch. Lanham, MD. Scarecrow Press. (1998), p. 145

85 Arch Oboler to Claude Raines. December 7, 1942. Box 15, Folder 5. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

86 Oboler’s telegram to Raines suggests that he thought the war would soon be over. Did he fear that the US would make a separate peace with Hitler and Mussolini?

87 “Oboler GM Footage to Metro as Stock Shots” The Film Daily. July 13, 1943. p. 20

88 Joel and Ethan Coen’s film, Hail, Caesar! (2016) is loosely based on the life of Eddie Mannix (played by Josh Brolin). See Newland, Christina. “The Truth About the Tyrannical Hollywood Fixer Who Inspired ‘Hail, Caesar!’ “. Vice Magazine. March 15, 2016. Retrieved from: https://www.vice.com/en/article/real-eddie-mannix-hail-caesar/

89 Arch Oboler to Edward Mannix. July 1, 1943. Box 15, Folder 5. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

90 “Oboler GM Footage to Metro as Stock Shots” The Film Daily. July 13, 1943. p. 20

91 MGM to A.W. Hackel and Edward F. Finney. December 27, 1943. Box 5, Folder 4. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

92 Hackel was an independent producer, mostly of low budget Westerns, who formed Supreme Pictures Corporation in 1934.

93 Edward F. Finney was also an independent producer. He’d made a successful series of singing cowboy films with Tex Ritter.

94 Max. M. King was also a producer of low budget films.

95 Hackel, Finney, and King to Arch Oboler. March 21, 1944. Box 5, Folder 3. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

96 This change makes Oboler’s film more like Sinclair Lewis’s novel It Can’t Happen Here (1935) and its television adaptation, Shadow on the Land (1968).

97 Arch Oboler to Danny Winkler. March 2, 1944. Box 5, Folder 3. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

98 Elite Pictures Corporation was the distribution arm of Supreme Pictures Corporation.

99 At the time, it was a common joke that Producers Releasing Corporation, abbreviated PRC, stood for “Pretty Rotten Crap”.

100 M&A Alexander Productions acquired a number of post-1938 films from the ultra low budget studio Monogram Pictures.

101 Finney, King, and Oboler to A.W. Hackel. January 25, 1952. Box 5, Folder 3. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

102 In a strange coincidence about injustice, Ohio doctor Sam Sheppard was watching Strange Holiday on television the night that his pregnant wife, Marilyn Reese Sheppard, was murdered. Sheppard was wrongfully convicted of his wife’s murder in 1954 and the conviction was overturned in 1966. His story formed the basis of the television show and film, The Fugitive. While identifying film elements of Strange Holiday with an archivist at the Library of Congress, I mentioned this story to him. He replied, “Dr. Sheppard was our family doctor. He was a lovely man. If you knew him, you knew he could never have killed his wife.”

103 A.W. Hackel to Arch Oboler. August 18, 1952. Box 174, Folder 4. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

104 Crowther, Bosley. “Oboler Film Opens at Rialto” The New York Times. October 20, 1945. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/1945/10/20/archives/the-screen-paris-underground-constance-bennett-production-new-bill.html

105 “Dictated letter to Congressman Frederick C. Smith.” 1946. Audio. RZC 4882. Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress.

106 Id.

The first entry in Matt Rovner’s series on Arch Oboler can be read at Part I: A Vanished Mystique. A third chapter in the series will be forthcoming.

August 2, 2025

(7368oboCS)

Visit CineSavant’s Main Column Page

Glenn Erickson answers most reader mail: cinesavant@gmail.com

Text © Copyright 2025 Matt Rovner

CineSavant Text © Copyright 2025 Glenn Erickson